William Hollander

Sometimes music takes a long time to develop. Often, in spite of all our efforts to make something creative happen on demand, it just takes years for ideas unfold. That is very much the case with this song that I refer to as William Hollander.

Somewhere close to five years ago I was playing a seisiún at The Skellig in Waltham where I heard an Irishman named Tony sing a song. An amazing song. For ten minutes he sang for the Skellig patrons, entirely acapella. His voice strained as he reached for notes describing his childhood, his loving parents, becoming bound to a butcher, a merchant sailor, a slave trader, a pirate, a condemned outlaw denouncing piracy and whiskey. It was a sprawling song that wove a tapestry of imagery, some beautiful, some appalling. I was stunned.

I had to have this song. After buying him a pint or two I asked him to repeat the melody for me while I scratched the notes onto the back of a napkin. He kindly agreed to email me the lyrics the following day, which he did.

The moment I picked up a guitar to try the melody I knew what to play. That part unfolded quickly. But the lyrics were another story. Tony’s version had thirteen verses and some renditions have up to nineteen verses. Far too many for me to a) remember and b) be able to retain anyone’s attention. I had learned this lesson from another well known song that I sing called Arthur McBride, which has, depending on how you count them, eight to sixteen verses. That is a long time to keep people interested.

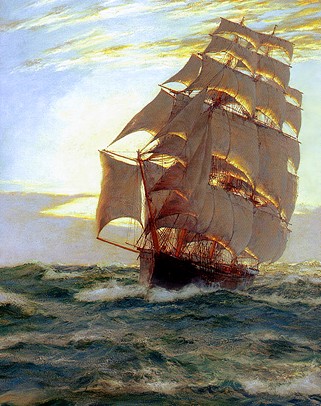

The original song, often called The Flying Cloud, has a mysterious origin. The real Flying Cloud is a famous clipper merchant ship that made a miraculously speedy run in the 1850’s from New York, around the horn and to San Francisco in 81 days and 21 hours. Her speed record stood until 1989. The song, however, speaks of piracy and slave trade, which is not part of the Flying Clouds true history. It is, therefore assumed, that the song grew like any great tale. The story gets bigger and better as time passes, which may account for the vast ground the song tries to cover. So many themes in one song are rarely found in modern music, especially without a repeating chorus.

So, I was faced with a dilemma. How do I distill the song down to capture its essence and do so in a manner where I am capable of selling the performance? For years I have mulled over this question. I have tried dropping verses and rewriting verses but have never really been happy.

The version that I’ve recorded here is my first real demo of it with newly revised lyrics. Like other projects that I’ve posted on baconworks, I expect that this is going to take on a life of its own and that this version will not be the last. And, true to the form of folk music, will continue to evolve.

…I was going to post the above earlier today, but before I got a chance my fellow musical Junkie Luke broke into my office, stole the track and worked his bass magic. Take a listen to how the bass changes to reflect the story of each verse, brilliant.

Also, there are already plans in the works to add Mustchio’s killer bouzouki part, and Beave’s bodhran.

William Hollander by baconworks